Dojo Kun

Origins & Philosophical Interpretation

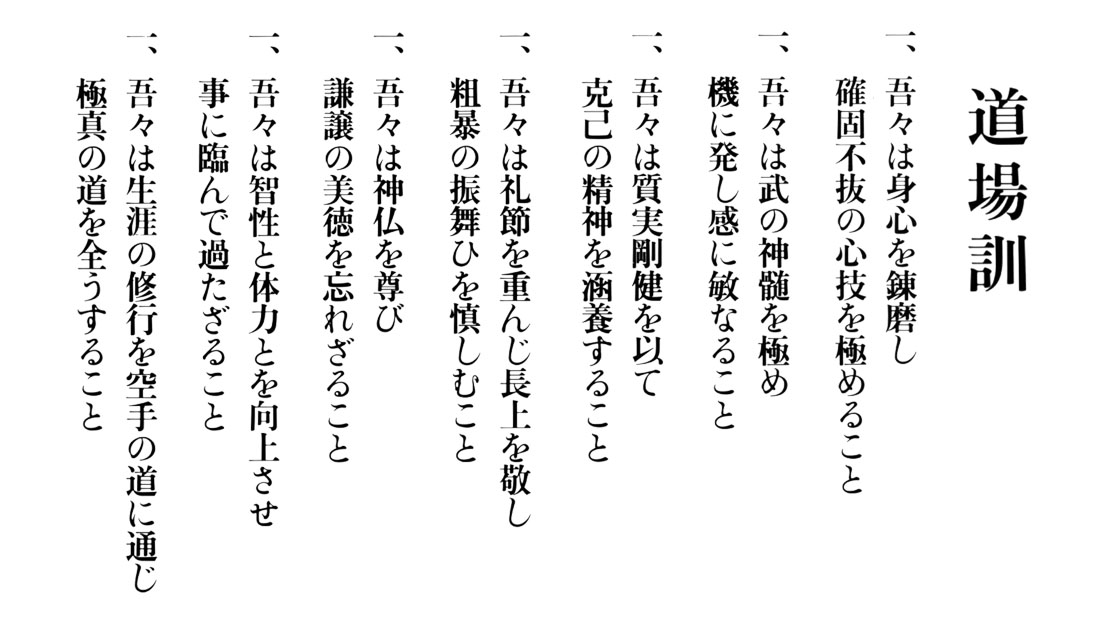

Dojo Kun in Japanese

After Sosai founded the Kyokushin style (officially in 1964 with the International Karate Organization Kyokushinkaikan), the Dojo Kun became a cornerstone of the organisation’s identity.

At the end of each training session, the class lines up in seiza (kneeling), and the highest-ranked student or instructor calls out each line, which the class repeats in unison. This ritual reinforces the values that drive our Kyokushin training. Note that Hitotsu (One) is said before each line to remind everyone that each rule is number one as all are equally essential.

In essence, the historical origin of the Dojo Kun is a blend of Mas Oyama’s personal martial journey and the timeless codes of conduct from Bushidō and Zen. It was Oyama’s way of ensuring Kyokushin Karate would always be practiced not just as a fighting system, but as a Way (Do) of life guided by honour, discipline, and truth.

Origins

The Dojo Kun has its roots in the vision of Sosai Mas Oyama, and reflects the influences of Japanese martial tradition that shaped him. Mas Oyama authored the Dojo Kun in the 1950s with the help of his friend Eiji Yoshikawa, a famous Japanese novelist. Yoshikawa was the author of the novel Musashi, a fictionalised account of the life of legendary samurai Miyamoto Musashi. This collaboration is significant: Yoshikawa’s knowledge of samurai ethos helped infuse the Dojo Kun with Bushidō (the samurai code) values and a classical tone. In fact, Mas Oyama greatly admired Musashi; during his own intensive training, Oyama carried and studied Musashi’s book Go Rin no Sho (The Book of Five Rings).

Through Yoshikawa’s novel and friendship, Oyama gained a deep understanding of the Samurai Bushidō code and its meaning. which ultimately shaped his karate philosophy. The Dojo Kun was born from this melding of Oyama’s practical martial experience and the bushidō principles gleaned from history and literature.

The Dojo Kun is written and recited in the first person plural pronoun “We”, which reinforces the dojo as a family; a community of shared values.

We will train our hearts and bodies for a firm unshaking spirit.

We will pursue the true meaning of the Martial Way, so that in time our senses may be alert.

With true vigor, we will seek to cultivate a spirit of self denial.

We will observe the rules of courtesy, respect our superiors, and refrain from violence.

We will follow our spiritual principles and never forget the true virtue of humility.

We will look upwards to wisdom and strength, not seeking other desires.

All our lives, through the discipline of Karate, we will seek to fulfill the true meaning of the Kyokushin Way.

Reciting the Dojo Kun in the first person singular pronoun “I” transforms it from a shared code of conduct into a personal affirmation.

I will train my heart and body for a firm unshaking spirit.

I will pursue the true meaning of the Martial Way, so that in time my senses may be alert.

With true vigor, I will seek to cultivate a spirit of self denial.

I will observe the rules of courtesy, respect my superiors, and refrain from violence.

I will follow my spiritual principles and never forget the true virtue of humility.

I will look upwards to wisdom and strength, not seeking other desires.

All my life, through the discipline of Karate, I will seek to fulfill the true meaning of the Kyokushin Way.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, shinshin o renmashi, kakko fubatsu no shingi o kiwameru koto.

We will train our hearts and bodies for a firm, unshaken spirit.

Kyokushin karateka are taught to forge both the body and the mind (hearts and bodies) through rigorous training. The aim is to develop an unshakeable spirit – a state of inner fortitude that cannot be easily disturbed by fear, pain, or self-doubt. This line stresses perseverance and resilience: by conditioning ourselves physically and mentally, we gain a firm spirit that remains calm and determined in the face of adversity. In practice, this means pushing through difficult training sessions and life challenges to strengthen one’s character. It reflects the idea that true strength in martial arts is not just muscular power, but a steadfast spirit that endures hardship.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, bu no shinzui o kiwame, ki ni hasshi, kan ni bin naru koto.

We will pursue the true meaning of the Martial Way, so that, in time, our senses may be alert.

This principle emphasises an ongoing quest to understand the essence of the martial way (bu no shinzui or the true meaning of Budo). Kyokushin practitioners should not train blindly, but with mindfulness and curiosity about the deeper principles of karate. By pursuing the true meaning of karate, over time, one cultivates heightened awareness – one’s senses become alert. In a literal sense, this means developing quick reaction, intuition, and situational awareness in combat. Philosophically, it suggests that through diligent study and practice, one gains insight and wisdom. The line implies that karate is more than physical techniques; it’s a path to sharpen one’s mind and spirit. An alert mind is ready to respond to any situation in life with clarity and instinct born from true understanding of the martial way.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, shitsujitsu gōken o motte, kokki no seishin o kanyō suru koto.

With true vigour, we will seek to cultivate a spirit of self-denial.

The phrase shitsujitsu gōken implies a spirit of fortitude and sincerity and training with seriousness and strength. With this genuine vigour, students must cultivate kokki no seishin, which means the spirit of self-denial or self-restraint. This principle is about self-discipline; pushing ourselves earnestly while also conquering our ego and desires. In the dojo, this is reflected in rigorous training that demands sacrifice – enduring pain, fatigue, and discomfort without complaint in order to improve. It means giving up laziness or ego-driven behaviors (like seeking immediate gratification) for the sake of mastery. In life, a spirit of self-denial translates to self-control and willpower; resisting temptations that stray one from their goals or values. This echoes the stoic mindset and Zen-like austerity in Kyokushin; by denying the self’s weaknesses, one strengthens character. Ultimately, this line teaches that true strength comes from mastering oneself.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, reisetsu o omonji, chōjō o keishi, sōbō no furumai o tsutsushimu koto.

We will observe the rules of courtesy, respect our superiors, and refrain from violence.

This principle highlights the fundamental ethics and etiquette expected of a martial artist. Reisetsu means etiquette or propriety, thus, practitioners must hold courtesy in the highest regard. They should respect their superiors (chōjō refers to seniors or those above in rank/position) which in the dojo means obeying instructors and senior students, and in life extends to respecting elders, teachers, employers, and authorities. Refraining from violent behavior (sōbō no furumai o tsutsushimu) is crucial as karate skills must never be misused to bully or harm others out of anger. This line reflects the Bushidō virtue of rei (respect) and self-control. Even though Kyokushin is a very powerful, combative style, practitioners must remain polite and humble. In training, this is seen in the formal courtesies, for example, bowing to instructors and fellow students, saying osu with humility, and maintaining decorum. Outside the dojo, it means carrying oneself with politeness, treating others kindly, and avoiding unnecessary fights or aggression. A Kyokushin fighter is expected to be gentle in spirit and manner, despite their formidable skills.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, shinbutsu o tōtobi, kenjō no bitoku o wasurezaru koto.

We will follow our spiritual principles and never forget the true virtue of humility.

This principle underscores the importance of staying true to one’s spiritual or moral principles and practicing humility at all times. The term shinbutsu literally means gods and Buddha, reflecting both Shintō and Buddhist beliefs; essentially respect the divine or honour your faith. In a broader sense, Kyokushin encourages students to adhere to whatever ethical/spiritual principles they hold, ensuring their martial journey is grounded in morality. Alongside piety or principle comes kenjō no bitoku, the virtue of humility. No matter how skilled or strong one becomes, arrogance is discouraged as the true karateka remains modest. In the dojo, this could mean bowing to the Shinzen (dojo shrine) or a moment of meditation in respect for something greater than oneself, and always showing humility towards instructors and opponents. In daily life, it means remembering to be grateful and humble, never abusing one’s power. Mas Oyama intended Kyokushin karateka to be warriors with virtue; to have faith or morals as a guiding light and to remain humble, recognising that humility is a strength and virtue in itself.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, chisei to tairyoku to o kōjō sase, koto ni nozonde ayamatzaru koto.

We will look upwards to wisdom and strength, not seeking other desires.

This principle urges practitioners to continuously improve their intellect chisei and physical strength tairyoku and to focus on those noble goals rather than chasing shallow or selfish desires. Look upwards to wisdom and strength suggests that one should aspire to knowledge, understanding, and bodily health/power – the higher aims of training – and avoid being distracted by temptations like excessive wealth, status, or indulgence. The Japanese phrase koto ni nozonde ayamatzaru implies not making errors when faced with important decisions or tasks. In essence, by not coveting other desires, a karateka keeps their life on a correct path, guided by wisdom and strength gained through training. In the dojo, this principle is seen when students prioritise learning techniques and building strength where the focus is on self-improvement, not envy or vanity. In life, it advises one to value education, personal growth, and health over materialism or momentary pleasures. It aligns with the idea of living simply and purposefully, much like a samurai who values honor and skill above riches. By cultivating wisdom and strength, a person is less likely to make poor choices. This line reflects a mindset of focus and purity of intention in one’s journey.

Hitotsu, wareware wa, shōgai no shugyō o karate no michi ni tsūji, Kyokushin no michi o mattō suru koto.

All our lives, through the discipline of karate, we will seek to fulfill the true meaning of the Kyokushin Way.

This principle ties everything together by declaring karate as a lifelong pursuit. Shōgai no shugyō means a lifetime of training/ascetic practice. Practitioners commit to walk the path of karatedo for their entire lives, using its discipline as the means to find the true meaning of the Kyokushin Way. Kyokushin, which literally means Ultimate Truth, is not just a style of karate but a philosophy of seeking ultimate truth and self-perfection. This principle reminds students that the lessons of Kyokushin are inexhaustible. Training does not end at a black belt or a trophy, it is a continuous journey of growth. Even outside the dojo one should live the Kyokushin values daily and keep improving oneself morally, physically, and mentally. It also emphasises perseverance over a lifetime, just as Sosai continued to train and teach into his senior years, each karateka should aim to carry the spirit of Kyokushin throughout their life’s journey, constantly striving to embody and understand its true meaning. This could involve teaching others, continually refining one’s technique and character, and facing life’s challenges with the indomitable spirit and humility that Kyokushin instills. In essence, this principle is a pledge to uphold the Kyokushin way of life forever, making karate not just an activity but one’s guiding way (Do). It encapsulates the idea that karate is a way to seek the ultimate truth about ourselves and life, and that quest lasts a lifetime.